A fatal polar bear attack in Svalbard, in the early hours of 28 August 2020 just outside the main town of Longyearbyen, is being unreasonably blamed on lack of sea ice. Details of the attack show it was made by a three year old male: such subadult bears are historically responsible for most attacks on people and they are known to be especially dangerous. It looks to me like someone should have seen this tragedy coming and stepped in to prevent it.

I will update this story as more information comes in but see below for the details known so far.

The attack

Camping site across from the airport in Longyearbyen. IcePeople

Details of the attack, from the CBC (28 August 2020), my bold:

A polar bear attacked a camping site Friday in Norway’s remote Svalbard Islands, killing a 38-year-old Dutch man before being shot and killed by onlookers, authorities on the Arctic island said.

Johan Jacobus Kootte was in his tent when it was attacked by the bear that killed him, deputy governor Soelvi Elvedah said. He was an employee of the Longyearbyen Camping site, where the attack occurred, the newspaper Svalbardposten said.

Kootte was rushed to the hospital in Longyearbyen where he was declared dead, Elvedah said.

The attack occurred just before 4 a.m. local time and was being investigated. No one else was injured, but six people — three Germans, one Italian, one Norwegian and one Finn — were hospitalized for shock, authorities said.

The polar bear was found dead in a parking lot by the nearby airport after being shot by onlookers, the governor’s office said in a statement posted on its website.

And from Icepeople (28 August 2020):

There have been at least four polar bears seen near Longyearbyen during the past week.

The bear that killed Kootte is a three-year-old male that was chased away from Hiorthhamn, a cabin across the bay from Longyearbyen, earlier this week, the governor announced Friday evening.

It is also the son of a female bear that was tranquilize [sic], along with her newest cub, and flown by helicopter to the northern part of Isfjorden after also making multiple visits the same location. The mother bear may be the same one that has made annual visits to the area in late summer and early fall, often with cubs, as part of her annual migration.

No other people at the campsite, who were all staying in tents, were physically injured by the polar bear, according to the governor. But six people were taken to the hospital in Longyearbyen and are being cared for by health personnel and city crisis managers.

An autopsy of the bear at a facility used by the governor is scheduled today. Because the fatality of a person was involved, the governor is requesting no photos of the bear be published by the media at this time.

The people at the campsite will be interviewed throughout the day as part of the investigation. The governor is asking people to avoid the area.

The campsite, typically open through early- to mid-September, was closed during the first half of the summer due to the COVID-19 crisis. While it is staffed during that period, and a building with kitchen and other facilities available, the campsite’s policy states guests are responsible for their own safety.

Although the campsite’s website states no bears have been at the site since the service building opened in 1985, a bear visited the designated bird sanctuary on the opposite side of the entrance road literally meters away (see YouTube video of visit at right) on July 29, 2011, only days after a fatal bear attack at a camp site about 40 kilometers away that was the most recent involving a person’s death in Svalbard.

Campsite policy states guests are not allowed to have loaded firearms there.

…

Nearly 40 comments were posted on the governor’s Facebook page during the hours following the attack, many of them expressing sympathy for the bear as well as the victim and other people there. At the top of those considered “most relevant,” Arek Stryjski, an experienced marine expeditioner in Svalbard, responded to someone upset about the lack of flare-alarm system by noting the risks it might pose in an area where large numbers of people might be present nearby.

“The camping in Longyearbyen is 500 meters from the airport terminal, (and) 100 meters from the parking and bus station,” he wrote. “Putting any flare alarms there will be dangerous for humans. It is miracle someone had loaded gun and more people where not hurt. What if it had attacked people who were leaving airport building?”

Van Dijk told Svalbardposten an electric fence was scheduled to be built around the campsite this year, and supplies arrived in March, but it was delayed when the COVID-19 crisis resulted in the shutdown of all visitors to Svalbard that same month.

“I was going to set up a three-wire electric fence with 200 poles around the entire campsite,” she told the newspaper.

So, there was no protection at the camp site from polar bears. And not only was the bear who perpetrated the attack a young bear who had never been on his own before but authorities knew he was out there, having been abruptly separated from his mother just two days before. Who could possibly not have seen a disaster coming? Sadly, the victim of the attack was sleeping in a tent on an exposed shoreline without an electric fence or a gun: he didn’t have a chance.

The Guardian (28 August 2020) offered this bit of additional insight (my bold):

„According to the local paper Svalbardposten, researchers at the local university field centre, Unis, avoid spending the night in tents near the shoreline – where the campsite is located – because of a recent increase in the presence of polar bears. „

Yet the BBC made this claim in their story on the incident (28 August 2020) about what unidentified ‚experts‘ say about polar bears in Svalbard (my bold):

„Experts say polar bears‘ hunting grounds have diminished as the Arctic ice sheet melts because of climate change, forcing them into populated areas as they try to find food.„

At least the writers at IcePeople talked to an actual polar bear specialist and included this quote from Norwegian researcher Jon Aars (my bold), who seems to be commenting on the fact that there were bears around in the first place:

Jon Aars, a polar bear expert with the Norwegian Polar Institute who frequently conducts research and advises the governor on polar bear incidents near settlements, told NRK the most recent incident most likely is part of a long-term trend of increasing bear activity near settlements due to vanishing sea ice elsewhere keeping them from tradition hunting sources.

“At this time of year, polar bears have extra challenges in obtaining food,” he said. “It has been a long time since there has been ice in the main hunting area, so there is less access to seals. So, the polar bear spends more time on land to find alternative food.”

I challenge this statement, given the details of this attack: “It has been a long time since there has been ice in the main hunting area.“ As I show below, there was ice in the area only a few weeks ago and most bears should have been in excellent condition (bears easily traverse the short overland distance from the east coast of Spitzbergen to the area around Longyearbyen on the west coast).

No mention from Aars about the inherent danger from young bears, the separation of this particular young bear from his mother, or about the higher than average ice levels around Svalbard this year in particular – see my comments below.

Sea ice Svalbard this year

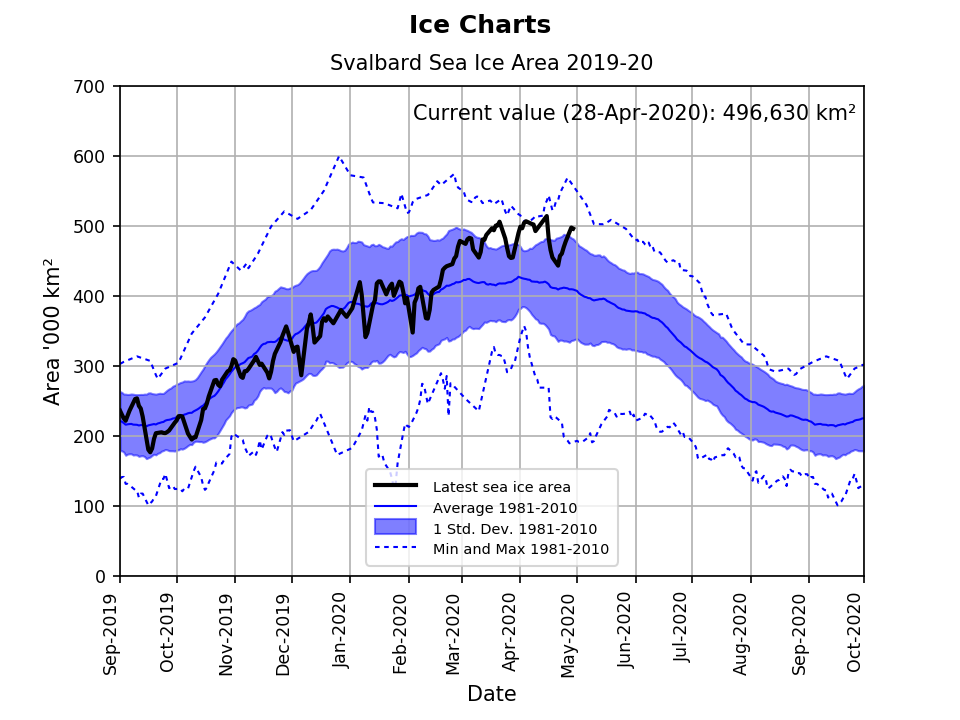

Far from having ‚low‘ sea ice, Svalbard ice conditions have been heavier since last fall than they have been in decades. In March this year, Svalbard had more polar bear habitat than it did two decades ago at the same date. By early April, the ice was the highest it had been since 1988 and by the end of April, Svalbard still had the 6th-7th highest ice extent since record began in the late 1960s. There was also exceptionally thick first year ice to the north.

In other words, Svalbard polar bears have had better sea ice conditions leading into the summer season than they have had in decades. And by early July (see below), there was still ice off the east coast of Spitzbergen:

It is certainly true that Svalbard in late August this year is lacking sea ice, even well north of the archipelago:

However, polar bears should have been well prepared for this event by virtue of the excellent ice conditions for feeding earlier in the year. Most bears onshore at the end of August should still be in excellent condition – except for young bears, as I explain below.

Svalbard area bears are thriving

Even without the ‚resurgence‘ of sea ice this year, polar bears have been doing extremely well despite the highest loss of summer sea ice of any other subpopulation. A recent study showed adult female bears in better condition in recent years than they were in 2004 (Lippold et al. 2020). Adult male bears are doing well also, with no real change over time (Aars 2018; Aars and Andersen, data posted online 2019). In short, bears chosing to spend the summer ashore on Svalbard should not be suffering any more than bears in Canada that find themselves spending their summers on shore, like Western Hudson Bay polar bears. Any well fed bear should be capable of spending 4-5 months on land over the summer. Except, of course, for young bears.

Young bears, such as the perpetrator of this attack (a 3 year old male), are the age/sex class most likely to attack humans. Subadults are the most disadvantaged group within the hierarchy of polar bears. They are likely to be food-stressed even when other bears are doing fine. Three year old bears are not fully grown, they lack hunting experience, and they are not strong enough to keep older, bigger males from stealing their kills during the spring feeding season (Amstrup 2003; Stirling 1974).

This age group are the most prone to attack people and are therefore almost always dangerous (Wilder et al. 2017). The danger presented by young bears is also part of what I have called ‚the problem no one will talk about‘ – what happens when there is a large, healthy population of polar bears with lots of mature adult males and no hunting allowed (Crockford 2019). Lots of adult males means young bears are stressed and extremely dangerous to people.

In this case, in my opinion officials should not have left this young bear to wander around a populated area after they had separated him from his mother. They had three options: kill him right away, capture him and relocated him as they did his mother, or keep a very close watch on his movements. They did none of those things. They could at least have warned the campers but it appears that did not happen either.

Not a single mention, in any of the media reports on this fatal attack, of how very dangerous young polar bears can be. Just false blame on sea ice. It’s like no one even bothers to look at the details of any individual polar bear attack: they just fall back on ‚climate change‘ as the villain every single time, which is not only uninteresting but misrepresents the facts.

References

Aars, J. 2018. Population changes in polar bears: protected, but quickly losing habitat. Fram Forum Newsletter 2018. Fram Centre, Tromso. Download pdf here (32 mb).

Amstrup, S.C. 2003. Polar bear (Ursus maritimus). In Wild Mammals of North America, G.A. Feldhamer, B.C. Thompson and J.A. Chapman (eds), pg. 587-610. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Crockford, S.J. 2019. The Polar Bear Catastrophe That Never Happened. Global Warming Policy Foundation, London. Available in paperback and ebook formats.

Lippold, A., Bourgeon, S., Aars, J., Andersen, M., Polder, A., Lyche, J.L., Bytingsvik, J., Jenssen, B.M., Derocher, A.E., Welker, J.M. and Routti, H. 2019. Temporal trends of persistent organic pollutants in Barents Sea polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in relation to changes in feeding habits and body condition. Environmental Science and Technology 53(2):984-995.

Stirling, I. 1974. Midsummer observations on the behavior of wild polar bears (Ursus maritimus). Canadian Journal of Zoology 52: 1191-1198. http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/abs/10.1139/z74-157#.VR2zaOFmwS4

Wilder, J.M., Vongraven, D., Atwood, T., Hansen, B., Jessen, A., Kochnev, A., York, G., Vallender, R., Hedman, D. and Gibbons, M. 2017. Polar bear attacks on humans: implications of a changing climate. Wildlife Society Bulletin, in press. DOI: 10.1002/wsb.783 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wsb.783/full

You must be logged in to post a comment.